Overview

Panel data tracks observations of individuals over multiple time periods, enabling researchers to uncover dynamic patterns that can't be observed in cross-sectional or time-series data alone. While traditional static panel data models assume that idiosyncratic errors are uncorrelated across time periods, dynamic panel models account for temporal dependencies in the data by including the lagged dependent variable as a regressor, often providing a more accurate representation of economic relationships. For example, current employment and wage levels are likely dependent on their past levels. Or, interest rates are very likely to be influenced by last year's interest rate.

This topic introduces the dynamic panel model and demonstrates how to estimate it, given that the estimation methods for panel data (e.g. Fixed Effects) are likely to produce biased results. After introducing the dynamic panel data model and System-GMM estimation, a simple example of estimation in R is provided.

Dynamic panel data model

A general form of the dynamic panel data model is expressed as follows:

where

- : Dependent variable for individual at time

- : Lagged dependent variable

- : Vector of independent variables

-

: Error term consisting of the unobserved individual-specific effect () and the idiosyncratic error ()

Summary

Key characteristics of the dynamic panel model:

- A linear functional relationship

- Dynamic dependent variable: A lagged dependent variable is included among the regressors

- Endogenous explanatory (right-hand) variables that are correlated with past and possible current error terms

- Fixed individual effects: Unobserved heterogeneity among individuals, which is another source of persistence over time

- Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation within individual units, but not across them

Including the lagged dependent variable provides a more accurate representation of the dynamic nature of the data. However, endogeneity is likely to arise, leading to what is known as the Nickell bias.

Nickell bias

As discovered by Nickell (1981), including the lagged dependent variable introduces endogeneity in the model due to its correlation with the error term. This can be expressed as:

.

As a result, standard panel data estimators like Fixed Effects, Random Effects, and First-Difference become biased and inconsistent. The coefficients of the lagged dependent variable () and other coefficients of interest () are potentially biased. The size of the bias depends on the length of the time period (T) and the persistence of the correlation, making the bias particularly significant in data with a short T and a large number of individuals (N). Increasing N will not decrease the bias.

Specifically, the Nickell bias leads to:

- Overestimation with OLS

Since the dependent varaible () is a function of the unobserved individual effects (), the lagged dependent variable () is also a function of . Therefore, is positively correlated with the error, which biases the OLS estimator, even if the idiosyncratic error terms are not serially correlated.

- Underestimation with Fixed Effects (FE)

The FE estimator eliminates through demeaning (within transformation). This transformation introduces a negative correlation between the transformed lagged dependent variable and the error term, resulting in a downward bias.

Tip

TipHow does this bias exactly occur?

The within transformation subtracts the individual mean from each observation:

where is the mean of the dependent variable for individual . The same transformation is applied to the lagged dependent variable and the error term.

The transformed lagged dependent variable. , is still correlated with the transformed error term (), because the mean () contains a lagged error () that correlates with by construction.

Also, the transformed error term is correlated with the transformed lagged dependent variable, as its mean () includes .

Estimation with System GMM

System Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), introduced by Blundell and Bond (1998), addresses endogeneity by using lagged variables as instruments. It constructs valid instruments from both lagged levels and lagged differences of the endogenous variables, estimating a system of equations, one for each time period. The instruments vary across equations. For instance, in later periods, additional lags of the instruments are available and can be used.

Tip

TipDifference GMM vs. System GMM

Difference GMM is the original estimator that uses only lagged levels of the endogenous variables as instruments, while System GMM combines lagged levels and differences as instruments.

The two-step system GMM estimation process consists of: 1. First-differencing the variables to eliminate individual fixed effects 2. Instrumenting the differenced equations using lagged levels and differences of the variables.

Instrument validity

Instrument validity is crucial. The conditions for a valid instruments to satisfy are:

-

Relevance: Instruments must be highly correlated with the endogenous variables they instrument. Using sufficient lags can help to maintain this condition.

-

Exclusion restriction: The lagged instruments must be exogenous, meaning they are uncorrelated with the error term. The instruments should only affect the dependent variable through the endogenous predictor. This assumption generally requires theoretical justification.

-

Independence assumption: The instruments are independent of the error term. In System GMM, lagged levels and differences of the endogenous variables should be uncorrelated with future errors. Limiting the lag length can help avoid correlation with present errors to maintain this condition.

In practice, it is important to balance the number of lags to ensure sufficient relevance without introducing bias or violating the exclusion and independence assumptions.

To ensure instrument validity, the Sargan test can be used. It tests whether all the instruments used in the model are uncorrelated with the error term, i.e. whether they are exogenous. Additionally, the Arrellano-Bond test for autocorrelation of order 2 can help to ensure whether the differenced residuals are not serially correlated at order 2. More on this in the R code example!

Tip

TipFor more background on Instrumental Variable Estimation: - Intro to IV Estimation - Bastardoz et al. (2023): A comprehensive review of IV Estimation discussing valid instruments.

Example in R

To illustrate the estimation of a dynamic panel data model, we use an example adjusted from Blundell & Bond (1998). We are interested in the impact of wages and capital stock on employment rates. As current employment rates are expected to depend on the values of the previous year, a dynamic model is more suitable. The dataset consists of unbalanced panel data of 140 firms in the UK over the years 1976-1984. Specifically, the following model is estimated:

Where: - : Log of employment in firm in year - Independent variables include both current and lag values of log wages and log capital - : Fixed effects per firm - : Idiosyncratic error term

Tip

Tip-

The used instruments depend on assumptions about the correlation between the independent variables and the error term. In this case, wages and capital are expected to be endogenous, so they are also instrumented.

-

The dataset starts in 1976 because no employment data is provided for earlier years. Therefore, the first observation for each firm in the sample is not special, supporting the initial conditions restriction outlined by Blundell and Bond (1998). This restriction assumes that the initial observations of the dependent variable are not correlated with the individual-specific effects, which is crucial for the validity of the System-GMM estimation.

# Load the package and data

library(plm)

data("EmplUK")

# Estimate the dynamic model with Two-step System GMM

dyn_model <- pgmm(log(emp) ~ lag(log(emp), 1) +

lag(log(wage), 0:1) + lag(log(capital), 0:1) |

lag(log(emp), 2:99) + lag(log(wage), 2:99) +

lag(log(capital), 2:99),

data = EmplUK,

effect = "twoways",

model = "twosteps",

transformation = "ld",

collapse = TRUE

)

- Lags of the endogenous variables are used as instruments, specified behind the

|. effect = twowaysintroduces both firm and time fixed effects.model = "twosteps"uses the two-step GMM estimator.transformation = "ld"applies the first-difference transformation (a System GMM model instead of a Difference GMM).-

collapse = TRUEreduces the number of instruments to avoid overfitting the model.Tip

Refer to the pgmm documentation for further information on the arguments within this function.

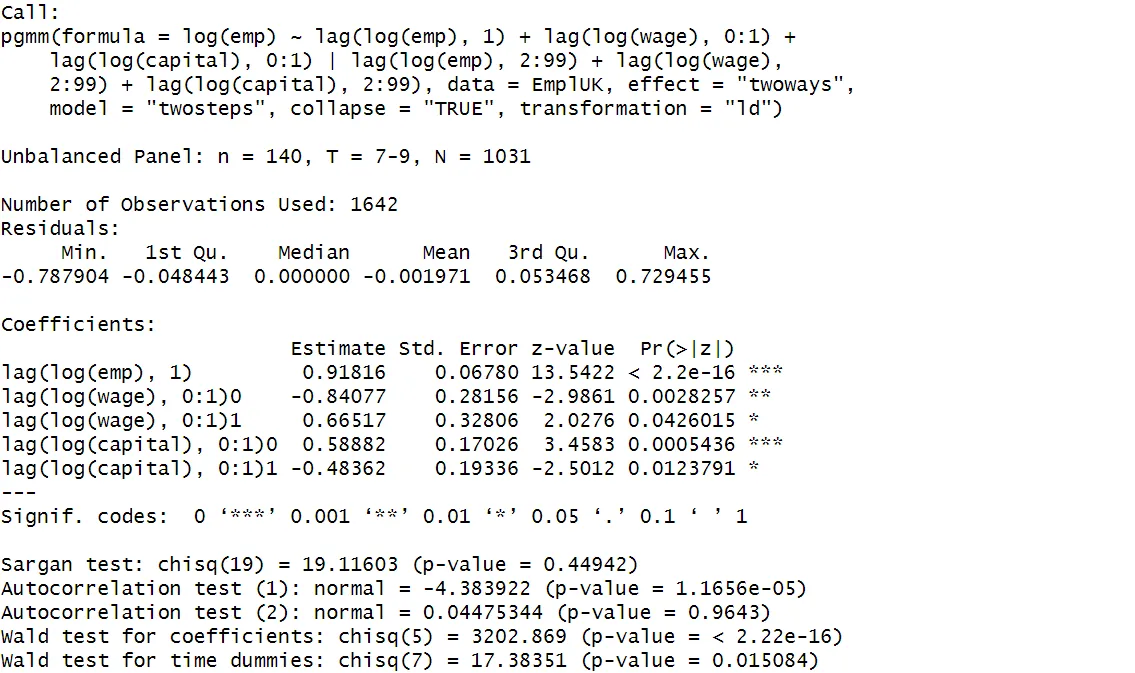

Interpreting the output

Employment persistence is found to be very strong, indicated by the positive coefficient of past employment levels that is statistically significant at a 1% level. Higher current wages seem to decrease employment, while higher past wages increase employment. Current investment has a positive impact, whereas past capital investments appear to negatively impact employment.

Tip

TipAs a useful check, consistent estimates for the endogenous dependent variable in the dynamic model should generally lie between the OLS and the FE estimates. This is because the OLS coefficient is biased upwards and the FE is biased downwards.

Diagnostic tests

The summary output gives some test diagnostics that help to assess the validity of the model.

-

Sargan test: Assesses the validity of the instruments. A p-value of 0.449 indicates the instruments are valid.

-

Autocorrelation test (1): Tests for first-order serial correlation. A p-value < 0.05 indicates that first-order serial correlation is present, as expected.

-

Autocorrelation test (2): Tests for serial correlation in the second order. The p-value > 0.05 indicates that second-order serial correlation is not present, which is consistent with the assumptions underpinning instrument validity.

-

Wald Tests: Assesses the joint significance of all the coefficients or time dummies in the model. The p-value < 0.05 confirms the coefficients and time dummies significantly affect the dependent variable.

All the test outcomes confirm the validity of the model. However, dynamic panel data estimators are highly sensitive to the specific model specification and the choice of instruments. Therefore, it is good practice to conduct several robustness checks and experiment with different model specifications, for example varying the lag lengths.

Summary

SummaryDynamic models account for temporal dependencies by including the lagged dependent variable, often providing more accurate results than static panel models.

A Nickell bias arises from including the lagged dependent variable as an explanatory variable, making standard panel data estimators (FE, RE, FD) inconsistent, especially in analyses with short T and large N. System-GMM estimation addresses this by instrumenting the endogenous variables with their lagged values.